Menu

This paper examines the impact of digitalization – the adoption of Internet-connected digital technologies and applications by companies – on B2B exchanges. While B2C exchanges are the subject of numerous studies on the transformations brought by the digital technologies, B2B exchanges are far less analyzed. Building on a conceptualization of exchanges between companies as made of activity links, resource ties, and actor bonds, this paper offers to identify three types of “digitalization” according to the nature of the most deeply impacted link.

Five cases of digitization in different industrial sectors and five companies providing digital solutions for businesses illustrate these three types. This typology provides an alternative to analyses based on the nature of digital systems used by B2B companies.

Digital technologies are progressively transforming B2B companies which have now access to a wide range of digital systems that can manage – or help to manage – their interactions with different actors of their network (Richard & Devinney, 2005).

Yet, how these systems are changing – or have already changed – the relationships a company has with its customers, its suppliers or with other actors of the business networks remain still unclear. Obal and Lancioni (2013) wrote: “while a great deal of published research on customer–firm relationships in the Digital Age has focused on end users and consumer markets, much less research has dealt with the impact of digital communications on the relationships between buyers and suppliers in industrial marketing.” (p. 851). The nature of change, the impact on business relationships and the problem identification related to these changes require appropriate theoretical lenses fine-tuned for a B2B context.

The aim of this work is to understand how digital technology impacts relationships into a business network and, consequently, how value is co-created by actors in the digital era. We define digital transformation as the digitalization of previously analog machine and service operations, organizational tasks, and managerial processes (Iansiti & Lakhani, 2014) in order to drive new value for customers and employees and more effectively compete in an ever-changing digital economy (Solis, 2017).

Our paper will be organized as follows. In a theoretical section, we show how the digitalization phenomenon refocuses attention on co- ordination and how a network approach is adapted to observe it. We use the literature on the actor –resources – activity model (Hakansson & Johanson, 1992; Hakansson & Snehota, 1995) to identify how changes in a network can be described in terms of changes at the level of activity links, resources ties, and actor bonds. We then describe five cases of digitalization in a B2B context and analyze them according to which of the actor, resource or activity layer of the B2B exchanges is impacted the most by the digital technology. Based on this analysis we propose a possible typology of these digital changes. Theoretical and managerial implications are developed.

Due to the complex nature of the digital market no single actor can provide a service to the customers with an end-to-end solution on its own, there is a need to sustain viable alliances and to create a value network with the right partners (Barnes, 2002; Canhoto, Quinton, Jackson, & Dibb, 2016; Pigneur, 2000; Sabat, 2002). Partnership management capabilities (Dyer & Singh, 1998) will have to be a core competence that new business actors must possess (Pigneur, 2000). Digital technologies are also transforming the structure of social relationships in both the consumer and the company space (Orlikowski, 1992). Furthermore, we need also to consider that products and services in- creasingly have embedded digital technologies (i.e. connected car or smart house appliances), and it is becoming more difficult to disen- tangle business processes from their underlying IT infrastructures (e.g., El Sawy, 2003; Orlikowski, 2009).

In this respect, some scholars (Fine, 1998) have proposed to address the challenge of the digital transformation following the “three-di- mensional concurrent engineering” framework adding value chain en- gineering to augment the traditional two-dimensional concurrent en-

gineering of products and processes (Fleischer & Liker, 1997; Nevins & Whitney, 1989; Ulrich & Eppinger, 1994). This framework focuses on the need to engineer a value chain simultaneously with the engineering of the products/services and processes for providing value. Significant value can be created assessing the value of relevant knowledge residing at different points in the network and arranging its transfer to other points in the network where it is needed (Doz, 1996; Gulati, 1999). This implies exploiting resources that are made available through the network relationship (Gulati & Singh, 1998; Inkpen & Dinur, 1998; Kale, Singh, & Perlmutter, 2000; Khanna,

Digital business strategies are then calling for coordination across firms along product, process and service domains, thereby creating complex and dynamic ecosystems for growth and innovation (Iansiti & Lakhani, 2014). The whole value network is underpinned by a particular value creating logic and its application results in particular strategic postures. Adopting a network perspective (Burt, 2004; Gulati, 1995; Kogut & Walker, 2001; Marsden & Podolny, 1990) provides an alternative perspective that is more suited to organizations, particularly for those where both the supply and demand chain are digitized (Peppard & Rylander, 2006).

In recent years, there has been considerable discussion and research about the impact of digital business strategies on the evolution of supply chains into value networks and value constellation or ecosystems (Iansiti & Lakhani, 2014; Pagani, 2013). The concept of “value network” has constituted a shift between a traditional vision of value creation anchored in a value chain perspective (Porter, 1985) to a renewed vision of value creation supported by the network perspective (Kothandaraman & Wilson, 2001; Möller & Rajala, 2007; Parolini, 1999).

Möller and Rajala (2007) building on Parolini (1999) precisely link the value network to a specific conception of how value is created and base the notion of value network on the idea that “each product/service requires a set of value creating activities performed by a number of actors forming a value-creating system”, there the value network. Bitran, Bassetti, and Romano (2003), define a value network as one in which a cluster of actors collaborates to deliver value to the end consumer and where each actor takes some responsibility for the success or failure of the network. This framework agrees with the concept of value con- stellation introduced by Normann and Ramirez (1993). According to this perspective, the value-creating system is composed of different economic actors who work together to co-produce value.

If value network has emerged as a central concept for research in digital contexts, scholars in industrial marketing have for a long time now promoted the use of a network approach to the study of B2B ex- changes. This is the case with the Industrial Network Approach or markets-as-networks approach (Gadde, Huemer, & Håkansson, 2003; Hakansson & Snehota, 1995; Johanson & Mattsson, 1992; Mattsson, 1997) associated with the Industrial Marketing and Purchasing (IMP) Group. But, as far as we know, the network approach of markets has not been discussed with a purpose of reporting on the general transformation of markets due to digital technologies.

The above-mentioned works all contend the idea that digitalization is profoundly changing the way business is carried out between companies. One important underlying dimension of the digitalization movement as analyzed by scholars is that it clearly refocuses on co- ordination between companies. Peppard and Rylander (2006) already emphasized more than a decade ago the impact of digitalization on the decline of transaction costs (whether transactions happen within or between companies). In such situation, when the access costs to external resources are low, the “integrated firm” is not offering any kind of specific benefit. Identifying external resources and having access to them becomes then the central issue. An issue that can be raised in terms of “coordination between companies”. More recently, Iansiti and Lakhani (2014) reaffirmed “coordination between companies” as a central issue with digitalization that is not a topic of “displacement and replacement but connectivity and recombination. Transactions are being digitized, data is being generated and analyzed in new ways, and previously discrete objects, people, and activities are being connected” (p. 93).

We thus build on the idea of the centrality of the coordination issues when dealing with digitalization and propose to use a framework that allows a detailed understanding of how companies get connected. The Actor–Resource–Activity model (Hakansson & Johanson, 1992; Hakansson & Snehota, 1995) provides the adapted framework.

The ARA model suggests that a business exchange can be described in terms of three “layers”: activity links, resource ties and actor bonds (Hakansson & Snehota, 1995). The model is able to capture “the complex connections between activity coordination and resource combining and the subsequent impact on the actor structure” (Mattsson, 2002, p 169).

ARA considers an activity as a “sequence of acts directed towards a purpose” (Hakansson & Snehota, 1995, p. 52). For instance, “developing a product”, “purchasing”, “selling”, “processing information”… are considered activities.

Resources sustain activities. Activities can be raw materials, physical facilities, components, operating systems, products… in short, “various elements, tangible or intangible, material or “symbolic”, can be considered as resources when use can be made of them” (Hakansson & Snehota, 1995, p. 132). Then, Håkansson and Waluszewski (2002) classify resources into four types: products and production facilities (which are both considered as technical/physical resources); organizational units and organizational relationships (which are considered social resources).

Actors interact with others to combine resources and link activities (Lenney & Easton, 2009). Actors in the ARA model can be individuals or organizations. The fact that a company can be considered an actor is to be linked to the idea that a company acquires an identity interacting with others (and not only because companies are considered – just like individuals – able to form intent, have purposes, be an agent).

Based on the above-defined “activity”, “resource” and “actor” concepts, any B2B relationship can be described following the way activities resources and actors are connected between firms. First, companies are connected by activity links, which concern technical, administrative, commercial and other activities of a company that can be connected in different ways to those of another company as a relationship develops. The rationale for more adjustments between activities is clearly ex- pressed as a gain in functionality: “the more adjustments, the more fine-tuned the two [activities] become in relation to each other and the better their performance” (Håkansson, Ford, Gadde, Snehota, & Waluszewski, 2009, p. 98). Yet, an excess of “linking” can also be detrimental as it impedes an activity to be reconfigured when new conditions arise (Håkansson et al., 2009, p. 127). At the level of the network, these connected activities shape an activities pattern.

Companies are also connected through resource ties that connect together various resources. Resource tying is the source of innovation: “resource ties cause some innovation in the use of resources and are important to the innovation potential of the company” (Hakansson & Snehota, 1995, p. 188). Yet, an excess of “tying” can have negative consequences by creating difficulties for the resource to be redeployed in a combination with other resources. At the network level, these connected re- sources form a resources constellation.

Finally, companies are interconnected through actors bonds that form a web of actors at the network level. Actors bonds are an important means for a company to mobilize other resources. Tightening bonds with a counterpart support a better access to information and resources. But, too much bonding can also be problematic as it “precludes interaction or bond formation with others” (Håkansson et al., 2009, p. 144).

These three layers of connection are not independent as there is an interplay between them. But the existence of bonds between actors is considered a prerequisite for the development of activity links and re- source ties.

The evolution of a business network can be described in terms of changes affecting whether the pattern of activities, the constellations of resources of the web of actors. Activities can be changed by new adjustments and coordination. The resource constellations can be modified when new combination occurs, and the web of actors is modified with actors changing their relationships one with another.

In this paper, we focus on how digital technology impacts differently on the activity links, resource ties, and actor bonds.

The aim of this study is to analyze how IT in the different functional components of the traditional B2B value chain influences the relation- ships by focusing on bonds and bonding processes and transforming progressively the value chain in a value network. This research employs case studies and in-depth interviews as more practical data collection and analysis level tools. Building on an ARA (Hakansson & Johanson, 1992; Hakansson & Snehota, 1995) representation of business net- works, we propose to analyze the changes provoked by digitalization according to which of the actor, resource or activity layer of the B2B exchanges is impacted the most.

The explorative survey was conducted by interviewing personnel in global companies having different size and ownership characteristics. The 10 semi-structures interviews (Stake, 1995; Yin, 1993, 1994) were conducted with the digital marketing manager and/or equivalent. The specific criteria for company selection were to provide a mixture of high tech versus manufacturing companies with a global presence; and at least one whose future was closely tied to broadband communication. We applied a case study approach (Yin, 1994) as it is the approach suggested when researchers require deeper understanding, solid con- textual sense, and provocation toward theory building (Bonoma, 1985). The companies belonged to five industries, all in the B2B: (1) chemicals and materials; (2) food and beverage; (3) healthcare and diagnostics (4) automotive, (5) insurance. We also conducted 8 semi- structured interviews with five companies providing digital solutions for businesses operating in 12 industries in order to explore further the impact of digital technologies.

Reliability was based on a detailed case study protocol that documented the scheduling, interview procedures, recording, follow-ups, questions, and summary database.

The research framework consisted of factors under the groupings of IT adoption, and utilization and the impact on existing activities and resources and the bonds with other players. In this paper, digitalization is considered as the companies adoption of IT-based solutions mainly using the Internet. Thus digitalization covers such things as EDI (Electronic Data Interchange) systems; websites; electronic market- places; extranets; electronic auctions; MRP (Manufacturing Resource and Planning) systems; ERP systems; RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) Systems; intelligent agent systems; etc. (Salo & Wendelin, 2013).

In this paper, we use the ARA model (Hakansson & Johanson, 1992; Hakansson & Snehota, 1995) to identify the different types of changes provoked by the digitalization of one or another actor in a business network. The digital technology and the different systems and tools that are supported by this technology are – according to the ARA model –considered as a resource. If considered by itself, a resource has no value.

Value – as far as resources are concerned – can only be created through the interaction of a resource with other resources. We thus propose to imagine the different “paths” the “digital resource” can follow and subsequently imagine different types of transformation brought by it.

The main data source consists of interviews (Arksey & Knight, 1999; Kumar, Stern, & Anderson, 1993). The interviewees were accordingly asked to briefly describe the company and to focus on one or more specific functional components of the value chain impacted by the IT. After that, they were asked to highlight the key people and events in the relationships. Finally, they specifically discussed the IT employed and how it has shaped the relationship. The choice of informants was premised on the principle that information is best elicited from people who have knowledge of the phenomenon and who have been involved with the relationship.

Altogether 18 semi-structured qualitative interviews have been done, each interview lasting an average of 1 h and a half. Interviews have been conducted with personnel inside each company in charge to implement a digital solution and in some cases also with the CIO. Key informants are critical to the success of case studies (Yin, 1994). The questions of the interviews were semi-structured in order to get the interviewee to answer the questions as completely as possible. The interviews were transcribed in order to get as much use of them as possible. Qualitative data analysis was employed in order to thematize the material (Miles & Huberman, 1984). Field notes of the reactions of people have also been made. Transcribing data and using field notes helped to achieve validity in qualitative research (Eisenhardt, 1989).

The researchers had in some cases also access to confidential in- ternal and external documents. In addition to interviews, documents, minutes of meetings, industry reports and internal documents provided by each company were also used to triangulate the respondents’ answers, as suggested in the literature (Patton, 1987; Yin, 1994). The validity and reliability of the research were increased with the use of data triangulation (Denzin, 1978; Eisenhardt, 1989).

In parallel a dataset of 30 B2B companies which have adopted digital technologies we also created. 7 main factors of analysis were considered (Industry, Type of technology, Function impacted, Declared benefits/barriers, Means of transformation, Extend of transformation) and 36 indicators. Companies included in the dataset belong to wholesale trade, advanced manufacturing, oil and gas, utilities, chemical & pharmaceutical, basic goods manufacturing, mining, real estate.

Founded in 2000, SpecialChem is a business and technical network in chemicals and materials engaged through dynamic relationships. This platform plays three main functions: 1) content provider (Webinars, industry news technical information); 2) technology enabler (open innovation; universal selectors; training from experts); 3) knowledge partner (newsletter, innovation polls). SpecialChem is connecting together more than 500,000 profiled members including advertisers, innovators, marketers and business developers. On the one side, they are developing a community of experts in a specific field or topic. These experts join the community because they have a free access to electronic newsletters, patent monitoring services, technical articles and online support services allowing fast question & answer interaction with leading experts in many specific technical fields. This technical support service (“TechDirect”) aims at answering questions within a period of 48 h. On the other side, they offer a Technology Scouting which aims at finding ready-to-use technologies used in external ap- plications/organizations to solve an internal technical challenge (Fig. 1).

Biomérieux is a company aiming at contributing to the improvement of public health worldwide through in vitro diagnostics. They offer Business Solutions for the management of infectious & cardiovascular diseases and they take the first position in clinical & industrial microbiology. They offer an integrated end-to-end product (tests, instruments, reagents, software & services…). The adoption of the digital technology inside Biomérieux is based on the principle that customer experiences drive customer perception and it changes how B2B companies sell and service customers. The digital strategy adopted by Biomérieux is to offer an omnichannel experience to their customers keeping the face to face interactions as a critical phase of the transactions. Their digital strategy is aimed at 1) increasing brand awareness and recruitment “…leveraging all customer touch points websites & others, the web, email, FaceBook, Twitter, Youtube, events sites” to promote the brand and increase recruitment; 2) driving market efficiency and empowering the sales force (“…with the right material for the right customer at right time on right device”); 3) maximizing customer loyalty (“…pro- vide customer online services that are accessible anytime, anywhere”).

The Coca-Cola Enterprises is the B2B side of Coca-Cola. It manages a franchising system with 12,000 collaborators (bottling companies) in EU (4400 UK, 5200 NEBY, 3400 FR) and a total of 1,000,000 retailers across CCE territories. The mission of The Coca-Cola Company is to own the brand, produce syrup and define consumer marketing strategy. Bottlers work closely with customers – grocery stores, restaurants, street vendors, convenience stores, etc. – to implement localized strategies developed in partnership with The Coca-Cola Company. They have a limited territory, produce the final product, define trade marketing (POS), sell and distribute products. The Coca-Cola Enterprises manage these complex relationships through a powerful CRM tool using new technologies and offering one customer view (through field sales activities, master data, reports, campaigns tool). The CRM system allows the company also to provide a useful Customer Portal (social media, website and mobile app) offering an efficient content to serve their ambitions and a connected system to optimize sell-out. The main benefits achieved can be summarized in 1) better customer knowledge, 2) operational efficiency, 3) cost improvement, 4) leadership vs. competitors (Fig. 2).

Volvo Construction Equipment (VCE) is one of the world’s largest manufacturers of construction machines. It proposes a full range of machines: loaders, excavators, scrapers, compactors, etc. Ten years ago the customers were continuously calling the service team, and the company considered itself as being only reactive: “we wanted to be proactive!”. Customers want predictability on the use of the machines because preventive maintenance and predictable downtime are important factors of performance. Proactivity means “having information about the use of our products”. But that kind of information (how an operator uses a product) is not easy to obtain, whether because it is difficult to collect that information or because the operator does not want to describe a usage that sometimes does not follow the guide- lines… (for instance, Volvo discovered that certain machine operators were using the reverse gear as a brake, or where overloading the loaders…). So the idea is to separate owners of the machines from in- formation on the machines. Machines are thus equipped with sensors and GPRS (mobile network) or satellite technology that are used to send information. In 2015 almost all machines are equipped and VCE now has “…tons of information about a machine”. Technology allows fault reporting and activity warnings; it facilitates remote diagnosis. For VCE the central idea is that the sooner problems are identified the faster they are resolved. Machine operation and deployment can be optimized via functions that monitor fuel consumption, location, hours of operation, speed, etc.

Renault Trucks offers commercial vehicle users a large choice of innovative services and vehicles (from 2.8 to 120 T) adapted to a wide range of transport activities: local delivery, regional distribution, construction, long distance, special applications, and defense. Renault Trucks vehicles are sturdy and reliable with low fuel consumption that enables them to deliver greater productivity and control operating costs. They use SAP which allows them to follow the truck in the manufacturing line, make invoices, analyze the sales, the productivity, margin. “…we can do it globally, only for a country, or even only for a dealer”. They are also implementing CRM allowing them to follow the activity salesman by salesman. “…we can analyze the market by competitors, by bodies, by weight of trucks, by running park”. For salesmen, this tool helps them to plan their prospection and contact their customer at a specific moment. The last IT tool that they are using is the apps and they offer some specific tools dedicated to the drivers to find easily the closest dealer, or to follow the truck consumption. We also have created specific apps for their sales force to help them on training, or on competitor knowledge.

The results emerging from the cases studies and the benchmarking were analyzed applying the ARA model in order to identify the different types of changes provoked by the digitalization of one or another actor in a business network. The digital technology and the different systems and tools that are supported by this technology are – according to the ARA model – considered as a resource. We thus propose to imagine the different “paths” the “digital resource” can follow and subsequently imagine different types of transformation brought by it. We classify the five cases we reported above, and the case study included in the benchmarking analysis, according to which types of “connections” be- tween actors they are primarily modifying. We identify three main types:

In this first type of digitalization, the digital resource is used to optimize already existing activities by supporting a better (easiest, cost- less) coordination between them. We choose to call this digitalization an “activity-links-centred digitalization” because the primary impact of the digital resource is on the links between activities. Activities that are better coordinated thanks to the digital technology can be “internal activities” or “external activities” (activities between two business actors). For instance, an EDI system does not fundamentally change the nature of the activity between two actors (the exchange of information) but allows doing it in a more efficient way. On the other hand, an MRP system does not change fundamentally the operations of a company but allows an effective planning of all necessary resources. We on purpose use the term “does not change fundamentally the activities” in the sense that activities are inevitably slightly modified, in different ways, by digitalization, but they can’t be considered “new activities”. The Biomérieux, Renault Trucks, and Coca-Cola Enterprises cases typically illustrate such a B2B digitalization. Biomérieux doesn’t change the sale activities but using digital devices to complete the B2B transactions allows a more efficient communication. Also Coca-Cola Entreprise, thanks to a digital CRM platform is now able to continuously monitor the clients and improve the relationship.

This type of digitalization is mainly characterized by a digital re- source supporting the creation of new activities carried out by already existing actors. We choose to call this type of digitalization of the net- work a “resource-ties-centred digitalization”. In that case, it is the combination of the digital resources possessed by one actor with the resources of another actor, which allows new activities to appear be- tween the actors. This phenomenon leads to the emergence of digital ecosystems (different players collaborate to create value). Connected objects are able to communicate to the manufacturing company in- formation about how they are used by the customer companies. On the basis of this information, the supplier is in a position to propose new services to the customers such as optimization of the use of products, training of operators, etc. This can be illustrated by the Volvo Construction Equipment case and confirmed by the two companies we further interviewed (IBM and Dassault Systems) providing digital solutions for businesses. For all these companies the digitalization re- presents a new resource (provided for example by companies as IBM or Dassault System) which allows to transform traditional business generating new activities. Dassault Systems works with different industries providing digital solutions that integrate and change existing activities (see digitalized diagnostic tools and augmented reality that allows doctors to explore the heart of the patient, 3D printing machines used to improve efficiency in different businesses, etc.).

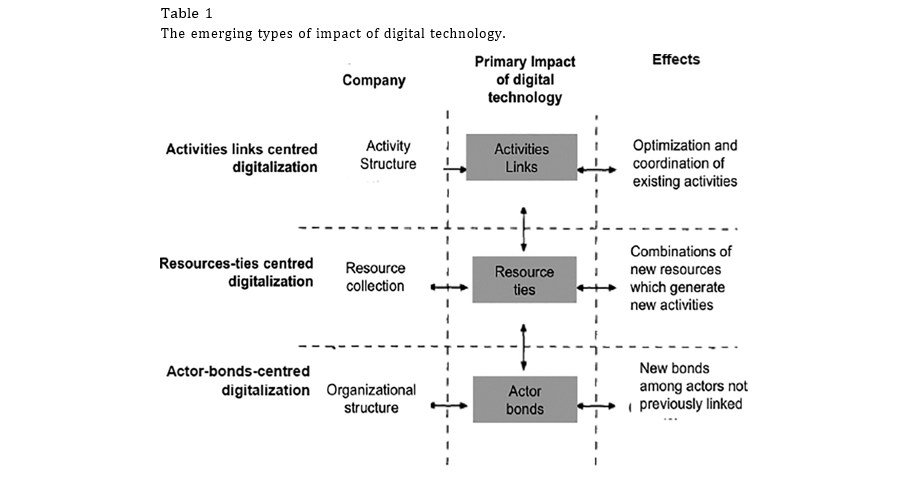

In this type of transformation, the digital resource supports new bonds between actors. We choose to call this digitalization an “actor- bonds-centred digitalization” because the primary impact of the use of the digital technology is to create new bonds between actors through a new actor taking a position in the network. In that case, the digital systems used by a new actor allow connections between actors that were not connected before or modify sufficiently enough the nature of the bonding. Take for instance a marketplace that uses the digital re- source to allow selling and buying companies to meet (what they may not have been able to do in the absence of the marketplace). This can be illustrated by the SpecialChem case which offers to chemical companies the possibility to be connected with other similar companies and benefit from the knowledge sharing (Table 1).

Our work is based on the statement that digital technologies are progressively transforming B2B companies, though it remains rather unclear how the relationships a company has with its customers, its suppliers or with other actors of the business networks are modified by these technologies. We made a proposal to classify digitalization according to three types, and we discussed for each type how value is specifically created. We contend that classifying digital transformation according to different types may contribute to a better understanding of the digital phenomenon within the B2B context.

Based on our multiple-case study and the typology of the impact of digital technology we are proposing, we consider the following four main theoretical implications.

First, though many B2B organizations are already successfully using digital marketing in specialist sectors, the B2B context is often considered as lagging behind the B2C one as an arena of digital changes and innovations. The first contribution of our work is that it theoretically frames digital transformation in a B2B context. This first contribution must be emphasized. We think that we have to be vigilant not to re-create an ex-ante dichotomy between B2C and B2B contexts by overlooking B2B digital transformations on the grounds that – because they do not directly involve the final consumer – are not so interesting as digital change phenomena. By focusing, in our typology, on changes in nature of exchanges between business actors we contribute to emphasizing what B2C and B2B situations have in common more than what distinguishes one from the other. Both in B2B and B2C digital technology may impact how value is created in the interaction between actors. We thus concur with Vargo and Lusch’s position on the idea of a central phenomenon to be observed in marketing: the one of value creation through resources integration. By “respecting” this unified view of marketing our typology both allow to re-integrate the B2B in the digital conversation without building on any type of B2C / B2B dichotomy.

Second, by building the typology on the basis of the modification of the interactions between actors – and not on the basis of the nature of the system used – we emphasize the role played by digitalization in the transformation of business networks. In recent years, several works have already been proposed with the aim of better understanding how digital technologies are changing the way companies are interacting in business networks, and, eventually how these business networks evolve. Yet, these works, most of the times focus on one digital tool, for in- stance social media (Brennan & Croft, 2012; Sood & Pattinson, 2012), e- commerce (Sila, 2013), or one activity sector for instance the steel industry (Salo & Wendelin, 2013), logistics (Rai & Tang, 2010), etc. Grounded in these studies, our contribution proposes an integrating framework that allows both positioning these different works in relation with each other and also identifying ways of change that are not yet fully experimented in B2B.

Third, our typology, because it is based on the modification of interactions between actors allows emphasizing the role played by digitalization in the value creation process. By focusing on how the digital technologies support new activity links, or new resources ties or new actors bonds, our work directly connects digital transformation to specific types of value creation. Each type of our typology corresponds to a specific type of value being created through new interactions brought by digital technologies. Value emerges whether through a process of activities rationalization (type 1), or through innovation based on new activities that emerge due to new digital resources (type 2), or through innovation due to new actors performing new activities (type 3). By doing so our work theoretically, relates digital transformation to value creation logics.

Fourth, by using the ARA model as a possible framework to read digital changes in a B2B context, our work contributes to prove the robustness of this model. We have moved the ARA model to new B2B situations brought by digital technologies. And we proposed to use it as a basis for our framework. By doing so, we are sharing the view of Cova, Pace, and Skålén (2015) writing that certain models “are not frozen but in a perpetual rejuvenation movement, which does not significantly affect their global architecture” (p. 682). This is an important theoretical aspect of our work that for new phenomena to be analyzed, brand new models are not absolutely necessary.

Our study has relevance for managers that we organize around three dimensions.

First, our work should definitely encourage managers to consider digital transformation as a value network issue and not a value chain one. The cases we have described show how digital technologies blur boundaries between supplier and customer companies (Renault Trucks); promote alliances between actors (see SpecialChem), allow upstream and downstream actors to connect directly (see VCE). Our vision of digital transformation may support managers’ change of mind and help them consider their companies and their surrounding environments as a global network where coordination creates complex and dynamic places for growth and innovation.

Second, digital transformations may sometimes appear unclear for certain B2B managers and B2B companies’ employees. “What exactly digital transformation means for my company?” may remain an un- answered or partially answered question for some people. By using our typology managers “translate” digital transformation in terms that resonate better for “non-IT experts”. Our framework by digging deep into the nature of digital changes gives managers an opportunity to better link these changes with B2B familiar dimensions: relationships, value, activities, and resources. By doing so, managers in charge of the digital transformation of their company are in a position to make employees much more familiar with and supportive of this transformation as they specifically see how they are involved in such a transformation. We invite managers to use the framework so as to qualify the digital changes of their company and, once the type of digitalization identified to translate it in terms of activities to be coordinated, resources to be combined or actors to be created.

Third, we think the framework we are proposing can also serve as a tool to “imagine” changes in a business network. We encourage man- agers to use the different types of digital transformations we have de- scribed to “read”, in a creative way, the network they belong to. Managers could, for instance, try to answer questions around three pillars: 1/ How can my company better coordinate – thanks to digital technologies – its activities with its customers? With its suppliers? With other actors? How can the efficiency of my company be improved with digital tools? (this set of questions may lead managers to identify the different activities interfaces within the company and with the different partners (customers, suppliers…) and discuss the possibility of their modification by using digital technologies) 2/ how digital technologies can facilitate new combinations of resources with my customers? My suppliers? Other actors? And thus opens on new activities to be developed (this set of questions lead managers to focus on what their partners (customers, suppliers, …) may value, with no limitation on the scope and nature of such value and assess is thanks to digital technologies such value creation is possible); and 3/ how can new actors appear in the network by taking over, thanks to digital technologies, activities that were traditionally carried out by other actors? (this set of questions may help managers to identify how activities can be differently divided up into a business networks thanks to digital technologies).

Beyond the different contributions presented above, we have to note several limitations of our work. Two of them are of significant importance and ask for more details.

First, we are quite aware of the extremely vast range of digital technologies that already exist and the very quick time of their evolution. We are also conscious that our typology can’t grasp any case of digital transformations. So the first limitation is due to the limited number of cases we have investigated and the limited knowledge we have of all technologies available for B2B companies.

A second important limitation is due to the approach taken in this study. By focusing on the impact of digital transformations on inter- actions between companies, we consequently left aside the internal aspects of digital transformations. Of course, activities – that are better coordinated by digital – can be internal activities; and resources – that are newly combined due to digital – are internal aspects of a company.

But what we did not deal with is the issue of how those companies, so as to allow new links, ties and bonds between activities, resources and actors have to adapt, for instance, by recruiting new digital talents (data scientists, date engineers…), or by creating new positions (Chief Digital Officer), or by proposing new KPI’s (to assess a salesperson that no longer sell when the customer company buys directly from a web- site…), etc.

Then, next steps of our research will lead us to collect more cases of B2B companies’ digital changes and check if our typology may capture all aspects of the digitalization journey. We do anticipate the possibility that further steps of research can change – at least incrementally – the framework we have proposed. Additionally, we plan to develop our typology in a complementary way by analyzing the internal characteristics or the companies belonging to the same type of our typology. Internal characteristics may include such elements as organizational aspects (formalization or centralization aspects), nature of capabilities held, the level of digital maturity.

Maadico is an international consulting company in Cologne, Germany. This company provides services in different areas for firms so they will be able to interact with each other. But specifically, raising the level of knowledge and technology in various companies and assisting their presence in European markets is an aim for which Maadico has developed … (Read more)