Menu

We investigate to what extent digital marketing strategies (such as having a digital marketing plan, respon- siveness to guest reviews, and monitoring and tracking online review information) influence hotel room occu- pancy and RevPar directly, and indirectly through the mediating effect of the volume and valence of online reviews they lead to, and to what extent this mechanism is different for different types of hotels in terms of star rating and independent versus chain hotels. The research was carried out in 132 Belgian hotels. The results indicate that review volume drives room occupancy and review valence impacts RevPar. Digital marketing strategies and tactics affect both the volume and valence of online reviews and, indirectly, hotel performance. This is more outspoken in chain hotels than in independent hotels, and in higher-star hotels than in lower-tier hotels.

Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) is “all informal communications directed at consumers through Internet-based technology related to the usage or characteristics of particular goods and services, or their sellers” (Litvin et al., 2008). eWOM can take many forms, the most important one being online reviews. eWOM has a profound effect on attitudes and buying behavior of consumers and on commercial results in many product categories, such as books (Chevalier and Mayzlin, 2006), movies (Duan et al., 2008a; Liu, 2006), online games (Zhu and Zhang, 2010) and restaurants (Kim et al., 2016). eWOM appears to be particularly important for experience products. These are goods or services the quality of which cannot be judged easily prior to consumption, like hotels (Casalo et al., 2015). In such situations, the opinion of other consumers who post their experiences in online reviews, provides information from a source that is perceived as more independent and trustworthy than company information (Zhao et al., 2015; Ye et al., 2011). In the travel industry, in the USA alone nearly two thirds of Web users relied on digital channels for travel information in 2013 (eMarketer, 2013). More than 74 percent of travelers use the comments of other consumers when planning trips (Gretzel and Yoo, 2008). Thus, online reviews are an important source of information for prospective hotel consumers, and they have an influence on trust and enjoyment (Sparks and Browning, 2011; Gretzel and Yoo, 2008), perceived credibility (Casalo et al., 2015; Mauri and Minazzi, 2013), hotel awareness (Vermeulen and Seegers, 2009), corporate reputation (Baka, 2016), attitudes (Casalo et al., 2015; Vermeulen and Seegers, 2009), hotel quality perceptions (Torres et al., 2015), booking intentions (Casalo et al., 2015; Ladhari and Michaud, 2015; Mauri and Minazzi, 2013; Sparks and Browning, 2011), hotel choice (Sparks and Browning, 2011; Vermeulen and Seegers, 2009), and willingness to pay (Nieto- García et al., 2017). As a result of this, online reviews also have an effect on hotel performance. Online reviews have been found to influence room occupancy, RevPar (revenue per available room), prices (Ögut and Tas, 2012; Ye et al., 2009, 2011) and market share (Duverger 2013).

Both the volume and the valence of online reviews affect consumer behavior (Kwok et al., 2017). Volume refers to the number of online reviews about a hotel in a given period; valence refers to the degree of positivity (rating) of these reviews (Blal and Sturman, 2014). More online comments have been found to lead to higher awareness (Zhao et al., 2015), and a better hotel performance (Viglia et al., 2016; Melián-González et al., 2013). The valence of online reviews also affects hotel performance. Ye et al. (2009, 2011) show that a 10% improvement in reviewers’ rating can increase sales by 4.4%. Anderson (2012) reports that a 1-percent increase in a hotel’s online reputation score leads up to a 0.89-percent increase in price, to a room occupancy in- crease of up to 0.54 percent, and to a 1.42-percent increase in RevPar. Viglia et al. (2016) report that a one-point increase in a hotel’s review score is associated with an increase of 7.5 percentage points in the occupancy rate. Viglia et al. (2016) and Torres et al. (2015) find that both ratings and the number of reviews had a positive effect on online hotel bookings. Blal and Sturman (2014) demonstrate that, contrary to the number of reviews, there is a significant impact of ratings on RevPar. However, very few studies have explored the potentially dif- ferential effects of review volume and valence on different indicators of hotel performance, such as room occupancy and RevPar.

An important question is what hotel marketing management can do to increase the volume and improve the valence of online reviews and, indirectly, hotel performance. Digital marketing strategies, such as closely monitoring and analyzing customer feedback (Torres et al., 2015), responding to customer feedback (Melian-Gonzalez and Bulchand-Gidumal, 2016; Sparks et al., 2016; Torres et al., 2015; Limb and Brymer, 2015; Wang et al., 2013; Levy et al., 2013; Chen and Xie, 2008), establishing a digital reputation management plan (Levy et al., 2013), monitoring and studying social media (Baka 2016; Levy et al., 2013) and integrating third-party review sites on the hotel website (Aluri et al., 2016) appear to drive online review volume and valence and/or hotel performance. However, Melian-Gonzalez and Bulchand- Gidumal (2016); Baka (2016) and Cohen and Olsen (2013) argue that further research is needed on how digital marketing strategies can en- hance reviews and improve organizational performance.

Finally, what drives online reviews and how and to what extent these reviews impact hotel performance may be different for different types of hotels. Blal and Sturman (2014) and Phillips et al. (2017) argue that hotel characteristics are contextual factors that play an important moderating role in consumer behavior. Viglia et al. (2016) point out that belonging to a hotel chain or being higher-star-rated could be factors that increases hotel occupancy. However, only a few studies have focused on the moderating effect of hotel characteristics on the effect of online reviews on hotel performance, for instance unknown versus well-known hotels (Casalo et al., 2015), higher versus lower-tier hotels (star rating) (Blal and Sturman, 2014; Duverger, 2013), and chain versus independent hotels (Banerjee and Chua, 2016).

In the current study we try to partly fill three voids in the literature:

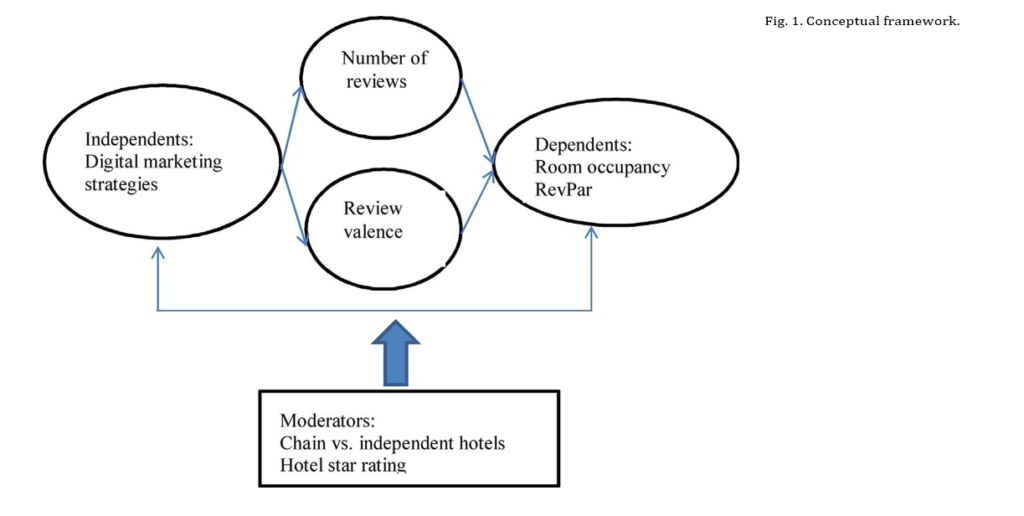

Sainaghi (2010) proposes to measure hotel performances on the basis of three dimensions: financial (e.g. RevPar), operational (e.g. occupancy or repeat visit) and organizational (e.g. customer satisfaction). The current study uses room occupancy and RevPar as the de- pendent variables, representing an operational (quantity of bookings) and a financial (quality of bookings) dimension, respectively (Torres et al., 2015). An interesting question is to what extent digital marketing strategies and the volume and valence of reviews impact these two KPIs differentially (Blal and Sturman, 2014). In the current study, we answer the call for a more fine-grained analysis of the managerial and online review drivers of two different hotel performance indicators. The conceptual framework is shown in Fig. 1. Data were collected from 132 hotels in five tourist destinations in Flanders (Belgium), by means of a combination of a survey, a hotel website analysis, and online review data.

The study offers several insights into how hotel marketing works and provides guidelines for hotel marketing practice. Sainaghi (2010) distinguishes between external and internal determinants of hotel performance. The current study considers both. First, although the influence of online reviews (an external factor) on consumers’ attitudes and behavior has been studied extensively, far less research has been reported on the influence of reviews on hotel performance. Studies that explore the effect of (digital) marketing strategies (an internal factor) on online reviews are also scarce (Sainaghi, 2010). Combining these two elements, the current study attempts to unravel the mechanism through which digital marketing strategies influence hotel performance, and the mediating role that volume and valence of online re- views play in this process. The current study also provides insights into the differential effects of digital marketing strategies and online reviews on hotel performance for different types of hotels, an important topic that only received scant attention (Sainaghi, 2010). The results of the current study can inform hotel marketing managers which elements of their digital marketing strategies to focus upon, what to expect from them in terms of their impact on different hotel performance indicators, and which online review elements should be monitored and taken into account in this process.

The number of reviews a product/service receives from customers is one of the most critical review attributes (Duan et al., 2008b). Several studies have shown that more online reviews lead to a better business performance (Viglia et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2016; Zhu and Zhang, 2010; Duan et al., 2008b; Amblee and Bui, 2007; Chevalier and Mayzlin, 2006; Liu, 2006). Torres et al. (2015) and Ye et al. (2009) find that the number of reviews have a positive effect on online hotel bookings. Kim et al. (2015) report that the number of reviews has a significant effect on hotel revenues. Tuominen (2011) finds a positive relationship between the number of reviews and a hotel’s RevPar and room occupancy. Viglia et al. (2016) report that, regardless the review score, the number of reviews has a positive effect with decreasing re- turns on the occupancy rate. The fact that review volume can positively affect business performance is attributed to the fact that reviews, positive or negative, are an indication of hotel popularity, increase consumers’ awareness of the product, keep the product longer in people’s consideration set, attract information seekers, reduce uncertainty and perceived risk, and trigger normative behavior (‘go with the crowd’) (Zhao et al., 2015; Viglia et al., 2014; Vermeulen and Seegers, 2009). This suggests that popularity per se has a strong relevance in terms of preferences (Viglia et al., 2016). Additionally, Torres et al. (2015) argue that, with greater number of reviews, the impact of extreme reviews is minimized.

Several studies have found that the valence of online reviews affects business performance. Positive consumer reviews increase business results, whereas negative online reviews decrease them (Anderson, 2012; Chevalier and Mayzlin, 2006). Positive comments can enhance the reputation of a company, while negative comments can reduce consumer interest in the company’s products/services, which can affect its profits. Sparks and Browning (2011) argue that the overall valence of a set of hotel reviews affects customers’ evaluations and trust and, consequently, booking intentions. Ye et al. (2009, 2011) show that positive online reviews can significantly increase the number of bookings in a hotel. They suggest that a 10% improvement in reviewers’ rating can increase sales up to more than five percent. Limb and Brymern (2015) find that overall hotel ratings predict RevPar. Anderson (2012) reports that a 1% increase in a hotel’s online reputation score leads to a room occupancy increase of up to 0.54 percent, and to a 1.42% increase in RevPar. Ögut and Tas (2012) show that a 1% increase in online customer rating increases sales per room up to 2.68% in Paris and up to 2.62% in London. In a study of 346 hotels in Rome, Viglia et al. (2016) found that a one-point increase in the review score is associated with a 7.5% point increase in the occupancy rate.

A few studies have assessed the impact of both the volume and the valence of online reviews on various indicators of hotel performance. In an online experiment, Nieto-Garcia et al. (2014) show a positive effect of review valence on willingness to pay for hotel accommodation, which is strengthened by online review volume. Viglia et al. (2014) conducted an online conjoint experiment and found that consumers’ preferences increased with both the number of reviews and the evaluation of the hotel. Torres et al. (2015) find that both ratings and the number of reviews on TripAdvisor had a positive effect on the average size of each online booking transaction. Each TripAdvisor star equated to an incremental $280 per booking transaction, and each review re- presented a total of $0.12 per booking transaction. Nieto-Garcia et al. (2014) find that both customer ratings and the number of reviews positively influenced profitability. Viglia et al. (2016) found a similar result for occupancy rate. On the other hand, Blal and Sturman (2014) and Limb and Brymer (2015) demonstrate that, contrary to the number of reviews, there is a significant impact of review ratings on RevPar. Using 56,284 hotel reviews posted for more than 1000 hotels listed on TripAdvisor, Xie et al. (2016) show that the effect of review valence lasts at least a couple of quarters, whereas that of review volume re- mains short-term. On the other hand, in the movie business, Duan et al. (2008a) found that the rating of online user reviews had no significant impact on movies’ box office revenues, but were significantly influenced by the volume of online posting.

The effects of a hotel’s digital marketing strategy on hotel performance, directly, or indirectly through its effect on online reviews, have only received scant attention in the academic literature (Cantallops and Salvi, 2014). Levy et al. (2013) and Melo et al. (2017) point out that hotels should establish a digital marketing plan, and that it is important for hotel managers to actively manage their online presence. In a digital hotel marketing plan, two main components can be distinguished. First, a hotel can actively use digital information in its marketing efforts in several ways, such as using information and metrics from review sites, providing a link to or integrating third-party reviews on its website, using track software to analyze reviews on OTA (Online Travel Agent) sites, or using OTAs management reports. Second, a hotel can have a conversation management strategy with its customers (for instance, responses to guest reviews, encouraging guests to post comments).

Several components of such a digital marketing plan have been explored in previous research. They are discussed hereafter. Information technologies (IT) have been recognized as one of the greatest forces causing change in the hotel industry (Law et al., 2013). Based on in-depth interviews with a group of 30 hotel managers, Melian-Gonzalez and Bulchand-Gidumal (2016) explore specific routes that IT can follow in order to improve hotel performance and argue that research is needed that clarifies how IT can improve this performance. Online feedback can help hotel managers track the attitudes, opinions, and satisfaction of guests and can serve as the basis for a series of management actions including responding to feedback, targeting in- vestments in services that consumers would desire, and perpetuating positive actions. Hotel managers who place greater value on consumer- generated feedback are more likely to improve the perceived hotel quality (Torres et al., 2015).

Aluri et al. (2016) studied the influence of embedding social media channels on hotel websites on traveler behavior. They find that travelers exposed to a hotel website with embedded social media channels have higher levels of perceived informativeness, enjoyment, social interaction and satisfaction and, indirectly, purchase intention. Casalo et al. (2015) find that online ratings are considered more useful and credible when published by well-known online travel communities, such as TripAdvisor, leading to more favorable attitudes toward a hotel and higher booking intentions. Consequently, making these reviews explicitly and readily available on the hotel’s website may have favorable effects on hotel performance. Melián-González et al. (2013) also argue that hoteliers should try to increase the number of reviews they receive and should therefore facilitate access to customer review sites.

The prominent role of social media necessitates that hotels also monitor online reviews for service recovery opportunities (Levy et al., 2013). Hotels are increasingly shifting from passive listening to active engagement through management responses. Online management responses are a form of customer relationship management (Gu and Ye, 2014). Management responses to a specific comment or a complaint in a consumer review show that hotel managers take their customers seriously, with the potential of improving customer reviews, customer satisfaction and, ultimately, hotel profitability (Sun and Kim, 2013; Chi and Gursoy, 2009). Various studies have explored the effect of responding to consumers’ remarks, and especially negative remarks or complaints. Gu and Ye (2014) show that the satisfaction level of consumers who made complaints in their reviews increases after they received management responses. Xie et al. (2014) report a positive effect of the number of management responses to consumers’ comments on hotel performance. They argue that these management responses will likely increase the consumer’s likelihood of recommending the hotel, and will consequently influence the behavior of prospective customers.

Hotel management can respond to comments and complaints in different ways. Xie et al. (2017) report that providing timely responses enhances future financial performance, whereas providing responses by hotel executives and responses that simply repeat topics in the online review lowers future financial performance. A constructive response with a service recovery plan for negative reviews and a commitment to continuous effort for positive reviews drives purchase decisions by subsequent consumers. Functional staff/departments, rather than executives, should provide managerial responses because their operational insights allow them to better address consumer comments. Sparks et al. (2016) find that the provision of an online response, the timeliness of the response, and using a human voice rather than a professional one enhances trustworthiness and perceptions of caring. Levy et al. (2013) also suggest that the best response strategy is a positive, personalized response within a short period of time. On the basis of an experimental study with students, Min et al. (2015) conclude that using empathy in response to a negative review improved online rat- ings. The response was also rated more favorably when the response was more personal and less generic. Responses should thus include a strong signal that hotels do read the complaints, rather than repeatedly duplicating generic responses. On the other hand, and contrary to claims made in other studies, in the Min et al. (2015) study, the speed with which the hotel responded to a complaint did not influence the ratings. This may be explained by the fact that most people who read managerial responses are not complaining customers, but potential customers for whom the time element is less important.

All in all, previous studies have investigated the impact of digital strategies and customer reviews However, as Kwok et al. (2017) argue, much of this previous work mainly had a customer-centric perspective, focusing on customer decision making and customers responses such as trust and satisfaction, and there is an increasing research interest into examining the determinants of online reviews and the effect of online reviews on business performance. As Phillips et al. (2017) state, a question that previous research leaves open is which antecedent factors influence both room occupancy and RevPar, and how this is explained by the online reviews they generate. In the current study, we explore 10 aspects of a digital marketing strategy, and their effect on online reviews and, ultimately, hotel performance. We expect each of these digital strategies to have a positive impact:

H1. The following digital strategies have a positive effect on room occupancy and RevPar:

These effect are mediated by both the volume and valence of online reviews.

Several researchers argue that hotel characteristics are contextual factors that may play an important moderating role in consumer be- havior, and call for further research into the effects of eWOM between different hotel categories (Phillips et al., 2017; Blal and Sturman, 2014; Cantallops and Salvi, 2014; Duverger, 2013).

Blal and Sturman (2014) report that review valence has a stronger effect on the RevPar of higher-tier hotels, while the volume of reviews has a greater effect on lower-tier hotels. The rating score effect on RevPar has little impact on the economy and midscale segments, while an increasing number of reviews actually has negative effects on higher-

end hotels. These results apply equally to chain and independent hotels. They argue that, as room rates increase with the segment, the im- portance of the nature of the review on the purchasing decision in- creases. On the other hand, in lower-end segments, potential buyers need confirmation that the room is as advertised, and they rely more on the number of prior experiences. Similarly, Ögut and Tas (2012) find that the effect of customer ratings on sales was stronger for higher- star hotels and, in the same vein, Duverger (2013) concludes that lower- tiered hotels should not seek a high review rating, because it is mainly highly rated hotels that benefit from it.

Banerjee and Chua (2016) studied differences in online reviews for independent and chain hotels, and find review patterns to differ substantially between them. However, they did not explicitly study what drives these differences and how they relate to hotel performance. Compared with an unknown, unbranded independent hotel, a well- known hotel chain brand name may attenuate the influence of rating lists, because the consumer already has stable beliefs about it (Cantallops and Salvi, 2014). Indeed, Vermeulen and Seegers (2009) find that especially for lesser-known hotels reviews increase consumers’ consideration of the hotel, and exposure to reviews has limited effect for well-known hotels.

In the current study, we explore the moderating role of hotel star rating and independent or chain hotels. Since previous research on the effect of hotel characteristics is scarce and contradictory, we propose the following research question:

RQ1. What is the moderating effect of hotel star rating and in- dependent or chain hotels on the relationship between digital mar- keting strategies, volume and valence of online reviews, and hotel performance (room occupancy and RevPar)?

The research was conducted in 2016 in the five officially recognized art cities in Flanders, Belgium: Antwerp, Bruges, Ghent, Mechelen and Leuven. On 31 December 2015, in those five cities, there were 224 li- censed hotels. 37.5% were chain hotels, the other ones were independent. The Flemish government assigns a star rating to each hotel. Sixty-six hotels were 1–2-star rated, the others were 3–4-star rated, except for one that was 5 star rated. In January 2016, all hotels in these five cities received a paper survey in which, amongst others, the number of realized room nights, and digital marketing activities were measured. One hundred and thirty-two hotels returned a fully completed questionnaire, a response rate of almost 59%. In this sample, there were 23 1–2-star hotels and 109 3–4 star hotels. The 5-star hotel refused to cooperate for confidentiality reasons. Consequently, there are no five-star hotels in our sample. The sample contains 72 chain hotels and 60 independent hotels. Additionally, an analysis of the hotel websites was made in which elements of hotel online behavior were captured.

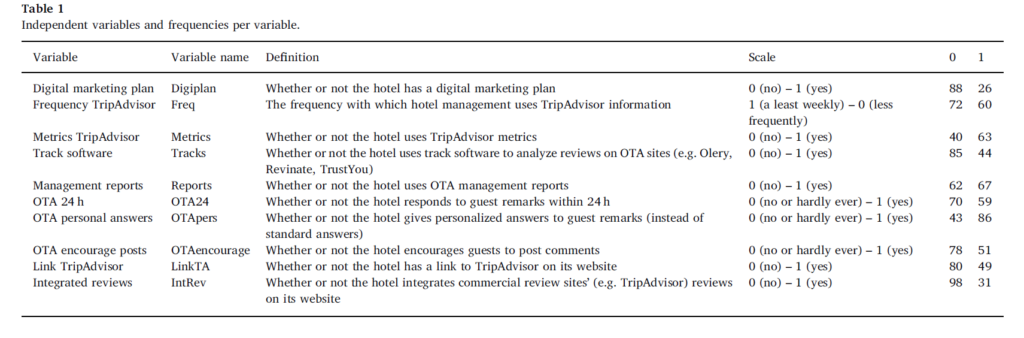

The dependent variables room occupancy (OCC) and RevPar were based on information reported in the survey. The list of independent variables (elements of a digital marketing strategy) was generated on the basis of in-depth interviews with 5 researchers from regional governmental or city tourism agencies, 2 representatives of hotel associations, 4 hotel tourism consultants, and 2 hotel managers (one 2-star and one 4-star hotel). The elements of digital marketing strategies are shown in Table 1. The first eight independent variables were measured in the survey; the last two were based on the hotel website analysis. The mediating variables, i.e. the number and valence of reviews in 2015 were made available by Olery, a company that tracks and analyses online reviews about hotels on more than 100 hotel review websites.

The valence of reviews is measured by means of the Guest Experience Index (GEI), Olery’s proprietary confidential measure that is based on review ratings and sub-ratings (for attributes such as rooms, cleanliness, location and service), the integrity of the reviews (based on, amongst others, the credibility of the site and the frequency with which a person posts a review), review age, and a sentiment analysis of the reviews. GEI is expressed as a score between 0 (very bad) and 100 (outstanding). The moderators, i.e. the number of stars (1 or 2 vs. 3 or 4) and the hotel type (chain or independent) are based on official government data.

The conceptual model in Fig. 1 was tested using Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macro for SPSS. Model 4 was used to test the basic mediation

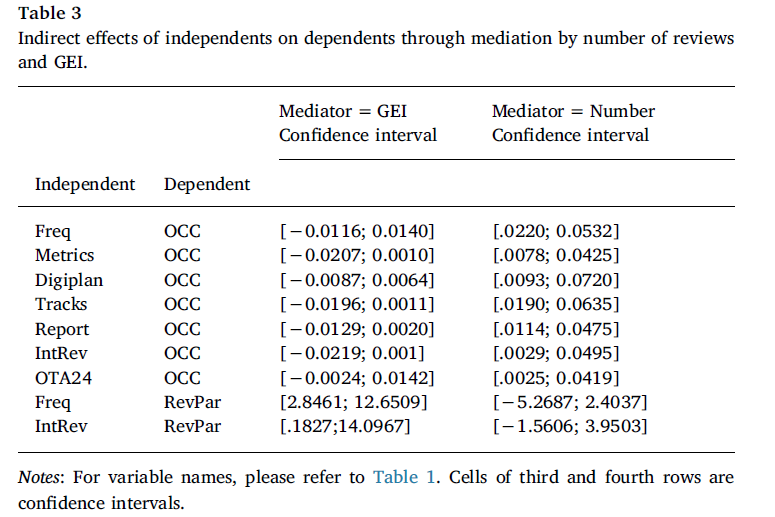

model. The Hayes procedure only allows models with one independent variable and one dependent variable. Therefore, in this first analysis, 20 models were tested, i.e. two (one per dependent variable) for each of the 10 independent variables. In each of these models, the number of reviews and the GEI were used as mediators. In Tables 2 and 3, the results of these estimations are shown. Only significant direct and in- direct effects of the independent on one of the dependents are reported. Full statistical details can be obtained from the authors. In Table 2, the effects and their significance of each path between each of the model variables are reported. The independent variables are in the columns and the outcome variables in the rows. The direct effects of the digital strategies on either OCC or RevPar are in bold. Table 3 reports the indirect effects of the independents on the dependents, through the mediation role of both the number of reviews and GEI. Each row refers to one model estimation. In the third and fourth columns of this table, confidence intervals are given. When a confidence interval does not contain zero, the indicated indirect effect is statistically significant (p < 0.05).

The frequency of TripAdvisor information used, using track soft- ware and integrating commercial review sites’ reviews on the hotel website have both a direct and an indirect effect on room occupancy, and thus their positive effect is partly mediated by the number of re- views these digital strategies generate. Using TripAdvisor metrics, having a digital marketing plan, using management reports and answering guest comments within 24 h only have an indirect effect on room occupancy, and thus the effect of these digital strategies on room occupancy is fully mediated by the number of reviews these strategies generate. H1a,b,c,d,e,f,j are supported as far as room occupancy and the mediating role of review volume are concerned. None of these effects are partly or fully mediated by GEI. H1 is thus not supported with respect to the mediating role of GEI on occupancy. A personalized response to guest remarks, encouraging OTA reviews and a link to TripAdvisor on the hotel website have neither a direct nor an indirect effect (through online reviews) on room occupancy. H1 g,h,i are not supported for room occupancy. The frequency of using TripAdvisor information has a direct positive effect on RevPar, and an indirect positive effect through GEI. Integrating reviews on the hotel website also has a positive indirect effect on RevPar, through its beneficial effect on GEI. H1b,j are supported as far as RevPar and the mediating role of review valence are concerned. The number of reviews does not mediate these effects on RevPar. H1 is thus not supported with respect to the mediating role of review volume on RevPar. H1a,c,d,e,f,g,h are not supported for RevPar.

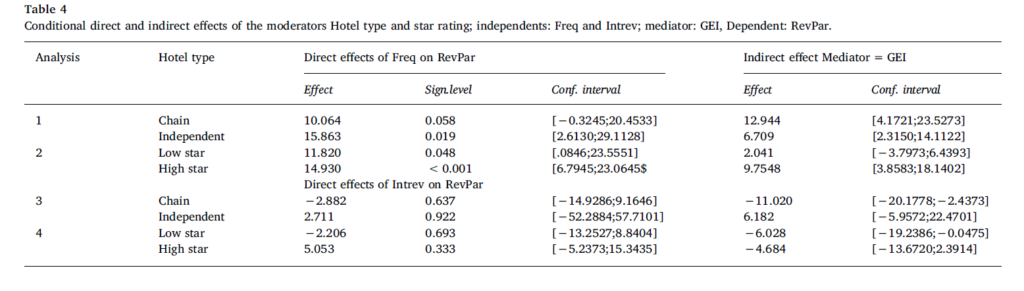

In the second set of analyses, we answer RQ1 by testing the moderating effect of the number of stars (1 or 2 vs. 3 or 4) and the hotel type (chain or independent) on the mediation process documented in the previous analysis, using Hayes’ PROCESS macro 59. We only made these moderation analyses on mediation models that showed significant effects (the 9 models reported in Table 3). We only report significant moderation effects. Full statistical details can be obtained from the authors. The main indicator for judging the meaningfulness of a moderation effect is the difference in conditional effect sizes (as detailed in Table 4 for RevPar and Table 5 for room occupancy) for the two different values of the moderators. Additionally, a clear indication of moderation would be that there is a significant effect for one of the values of the moderator, but not for the other. If a confidence interval in Tables 4 and 5 contains zero, the conditional effect is not significant for that value of the moderator. We have used these criteria to arrive at our conclusions. In Tables 4 and 5, the first column indicates the number of the analysis. The second column shows the two levels of the moderator. The next three columns show the direct effects of the independent on the dependent, for the two values of the moderator. The last two columns of each table show the effect sizes and the confidence intervals of the indirect effects through the mediator.

Table 4 shows that there is a direct positive effect of frequency on RevPar for independent hotels, but not for chain hotels. However, the indirect effect through generating a higher GEI score is stronger for chain hotels than for independent hotels (analysis 1). Both the direct and indirect (through GEI) effects of frequency on RevPar are stronger for higher rated hotels (analysis 2). The indirect effect (through GEI) of integrating reviews on the hotel website is negative for chain hotels, and insignificant for independent hotels (analysis 3). The indirect effect of Intrev on RevPar is negative for low star hotels, and not significant for high star ones (analysis 4).

Table 5 indicates that the direct effect of frequency on room occupancy is positive for independent hotels and not significant for chain hotels, but the positive indirect effect through the number of posted reviews is only significant for chain hotels and not for independent hotels (analysis 5). There is only a direct effect of frequency on room occupancy for high star hotels, but its indirect effect through the number of online reviews is stronger for low star hotels (analysis 6). There is no direct effect of the use of metrics on room occupancy, and the indirect effect is only significant for chain hotels (analysis 7) and high star hotels (analysis 8). The indirect effect (through the number of online reviews) of the use of track software on room occupancy is stronger for independent hotels (analysis 9), and both the direct and indirect effects are only significant for high-star hotels (analysis 10). The indirect effect of responding to guest reviews within 24 h (through the number of reviews) on room occupancy is only significant for high- star hotels. There is no direct effect of this strategy on room occupancy (analysis 11). The indirect effect of using reports on room occupancy (through the number of reviews) is only significant for chain hotels (analysis 12). The direct effect of integrating third party reviews on the hotel website is only significant for chain hotels (analysis 13). The in- direct effect of having a digital marketing plan (through the number of reviews) on room occupancy is only significant for high-star hotels (analysis 14).

Digital marketing strategies such as having a digital marketing plan, the frequency of TripAdvisor information used, using TripAdvisor metrics, using management reports, answering guest reviews within 24 h, using track software, and integrating commercial review sites’ reviews on the hotel website, all appear to affect room occupancy favorably, partly or fully because they lead to more reviews, and not because they increase review valence (GEI). Stated differently, the positive effect of the use of these strategies on room occupancy is partly or fully mediated by the number of reviews these activities generate. These results confirm previous findings on the role of review volume on room occupancy (Torres et al., 2015; Tuominen, 2011; Ye et al., 2009). Review valence does not affect room occupancy. This contradicts earlier find- ings by Ye et al. (2009) and Anderson (2012).

RevPar is affected by digital strategies to a more limited extent, i.e. only by the frequency of using TripAdvisor information and by integrating reviews on the hotel website. Both effects are mediated by review valence. This finding is in line with previous studies (e.g., Limb and Brymer, 2015; Anderson, 2012; Ögut and Tas, 2012). The fact that not the number of reviews, but their valence affects RevPar, is a confirmation of the findings of Blal and Sturman (2014) and Limb and Brymer (2015), but contradicts the findings of Torres et al. (2015) and Nieto-Garcia et al. (2014) in that the latter find an effect of both review volume and valence on hotel profitability.

All in all, most components of a digital marketing strategy considered in the current study affect hotel performance, partly or fully through the effect they have on the volume and/or valence of online reviews. However, this is more the case for room occupancy than for RevPar, and review volume mediates the effect of digital strategies on room occupancy, while review valence does so for the effect of strategies on RevPar. These results confirm Blal and Sturman’s (2014) claim that volume and valence of online reviews influence hotel performance parameters differently. The results also confirm the crucial role of IT strategies and, to a lesser extent, the importance of responsiveness and service recovery. As to the former, the present findings support the need for a formal digital marketing plan (Levy et al., 2013) and the impact of embedding social media channels and integrating reviews on the hotel website (Aluri et al., 2016; Melo et al., 2017). As to the need for responding to guests’ comments, only the speed of the response to comments seems to matter. This confirms previous findings (Xie et al., 2017; Sparks et al., 2016; Levy et al., 2013), although our results are not consistent with Min et al.’s (2015) conclusion.

Remarkably, a link to TripAdvisor on the hotel website, personalized response to guest remarks, and encouraging guests to post re- views, have no effect on either room occupancy or RevPar. The fact that a link to TripAdvisor does not stimulate reviews and improve hotel performance, contradicts the findings of Casalo et al. (2015) that well- known online communities lead to better attitudes and booking intentions. The fact that a personalized response and encouraging reviews from guests do not have an effect on reviews and hotel performance, contradicts several previous studies (Levy et al., 2013; Min et al., 2015; Sparks et al., 2016; Xie et al., 2017). This is an unexpected result that requires further study.

Of all digital strategies considered in the current study, the fre- quency of using TripAdvisor information and integrating third party reviews on the hotel website seems to be most important, since they have an impact on both the number and the valence of online reviews, which in turn leads to both a higher room occupancy and RevPar.

These mediation processes are moderated by the type (chain or independent) and the star rating of the hotel. A rather consistent result is that the effect of a number of digital strategies appears to be stronger for higher-star hotels, either in their direct effect on room occupancy or indirectly through their effect on the number of reviews posted, or both. This is the case for having a digital marketing plan, using metrics and track software, and responding to guest reviews within 24 h. Furthermore, both the direct and indirect (through GEI) effect of the frequency of use of TripAdvisor information on RevPar is stronger for higher-rated hotels, and the indirect effect (through GEI) of integrating third-party review sites is negative for lower-star hotels, and not significant for higher-star ones. These results confirm the findings of Ögut and Tas (2012) and Duverger (2013), and partly those of Blal and Sturman’s (2014). The latter find that review valence had a stronger effect on the RevPar of high-star hotels than on economy and midscale segments. However, their finding that review volume drives RevPar of lower-end hotels is not confirmed, quite the contrary, since our findings suggest that also the effect of review volume on room occupancy plays a stronger role for higher rated hotels.

The indirect effect (trough the number of reviews) of online strategies on room occupancy is generally stronger for chain hotels than for independent hotels. This is the case for the frequency of using TripAdvisor information, using metrics and reports, and integrating third party reviews on the hotel website. The indirect effect of the frequency of using TripAdvisor information on RevPar through generating a higher GEI score, is stronger for chain hotels than for in- dependent hotels as well. However, the effect of the use of track soft- ware on room occupancy rate is stronger for independent hotels, and so is the direct effect of frequently using TripAdvisor information on RevPar. Responding quickly to guest reviews has a negative effect on room occupancy for chain hotels, but not for independent hotels, and the effect of integrating third-party reviews on the hotel website has a negative effect on chain hotels, and no effect on independent ones.

Some of these results contradict Cantallops and Salvi’s (2014) and Vermeulen and Seegers’s (2009) findings, which are explained by the assumption that chain hotels have well-known brand names and are more familiar to the traveler, and that this may diminish the influence of online reviews. We believe that our results could be explained by the fact that chain hotels may have a more professional and sophisticated, and thus more powerful, digital marketing strategy, which leads to a greater impact of digital tactics on online reviews and hotel performance.

The managerial implications of our study are that hotel manage- ment should devote considerable attention to both the number and the valence of reviews about their hotel, and should develop an extensive digital marketing strategy that has a profound impact on these reviews and, directly or indirectly, on hotel performance. The first step in such a digital marketing strategy is to have a digital marketing plan that provides for online hotel presence, tracking and monitoring online re- views, and quick response to customer comments. Indeed, many components of such a plan have a significant impact on the volume and/or the valence of online reviews, and on hotel performance in terms of room occupancy or RevPar. This is especially true for chain hotels and 3–4 star hotels, for which the impact of digital strategies and tactics is, generally speaking, more outspoken than for independent or lower-tier hotels. Especially the frequency of using TripAdvisor information (re- ports and metrics) and integrating third party reviews on the hotel website is crucial, since these tactics increase both the volume of and the appreciation in online reviews and, as such, indirectly influence both room occupancy and RevPar positively. The TripAdvisor

Management Dashboard is an analytics service that summarizes a hotel’s performance on TripAdvisor. Hotels can use the data and in- formation to track how they are engaging with customers and guests online, target areas for improvement and make informed, decisions.

The dashboard provides, amongst others, reports on a hotel’s total re- views and popularity ranking over time and relative to the hotel’s competitors in the same geographical region, latest review activity and top comments from reviews, number of traveler and hotel-submitted photos, and the number of visitors viewing photos, most viewed competitors, the countries generating the most traffic to the hotel’s

TripAdvisor page, trends over time, and performance metrics.

TripAdvisor reports provide, amongst others, business trends, risk factors, financial data, and results of operations (www.tripadvisor.com). Additionally, hotels that strive for a higher room occupancy should aim at increasing the volume of online reviews This online review volume can be increased by increasing the frequency of using TripAdvisor metrics, by using track software and management reports, and by answering guest comments within 24 h. Hotels that want to focus upon RevPar need to improve the valence of online reviews.

Our study has some limitations that offer opportunities for further research. First, the current study was carried out in 132 hotels in five Belgian cities. Our findings should be corroborated in different countries and contexts and in larger samples. There were no luxury (5-star) hotels in our sample. Further research could also focus on this special hotel category. Second, two contextual variables are taken into account (independent versus chain and star rating), but different contextual factors could be considered, such as, for instance, the size of the hotel, the region in which the hotel is situated, and the type of visitors (e.g. business, leisure). In any case, the scarcity of studies on the influence of contextual factors on the effect of online strategies on reviews and hotel performance necessitates further research in this area. Third, volume and valence are the most frequently studied aspects of online reviews, but also other elements could be taken into account, such as the variance of reviews, the percentage of negative reviews, the topic of the reviews (hotel and service attributes, for instance), the degree of negativity and positivity of reviews, reviewer characteristics (demo- graphics, reputation expertise, experience), etc. (Kwok et al., 2017). Next, a number of digital strategies and tactics have been taken into account, but there could be other factors that stimulate the generation of reviews, such as service characteristics, hotel amenities, staff behavior, location etc. Their relative importance and how management strategies can enhance or attenuate their effects should be studied. Finally, the effect of managerial responses to customer comments should be studied further. Most studies to date investigate the effect of managerial responses on customer trust, concern, satisfaction, and attitudes. However, this research should be taken one step further, and explore the effect of managerial responses on hotel performance, and the mediating role of customer reactions in this process.

Maadico is an international consulting company in Cologne, Germany. This company provides services in different areas for firms so they will be able to interact with each other. But specifically, raising the level of knowledge and technology in various companies and assisting their presence in European markets is an aim for which Maadico has developed … (Read more)